5 Ecosystem processes and threats

5.1 Processes and interactions

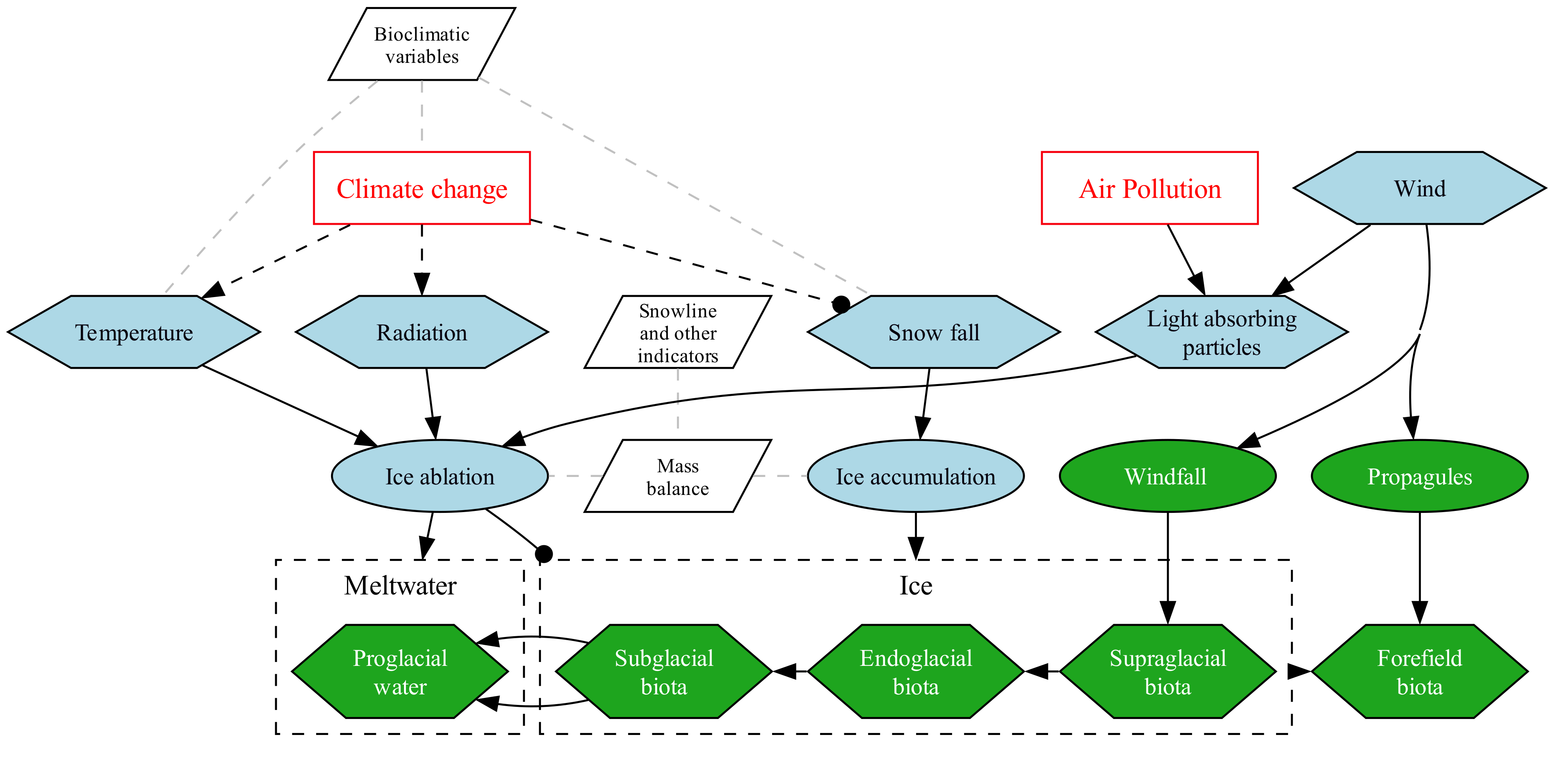

Tropical glacier ecosystem in the Cordillera de Mérida have a dynamic of ice accumulation and ablation influenced by precipitation (in the form of snow- or rainfall due to temperature fluctuations), temperature and solar radiation that can trigger annual and diurnal cycles of melting and freezing conditions, and the geomorphology that modulates the rate of basal melting and movement of the ice on top of the rocky substrate.

Mass balance of the icy substrate is likely dominated by interannual fluctuations (Andressen, 2007; Braun & Bezada, 2013), but no quantitative studies have been conducted. Substantial reductions in precipitation and higher exposure to solar radiation are expected with El Niño–Southern Oscillation years, while high precipitations and more cloud coverage are expected during La Niña years. However, these glaciers are believed to be out of balance (i.e. dominated by ablation that drives a continuing decline in ice mass and extent) due to their location near or even below theoretical equilibrium lines (Polissar et al., 2006; Braun & Bezada, 2013).

Reduction and fragmentation of the glacier ice extent makes them more vulnerable to scale and edge effects. When the glacier is below a critical size they are more exposed to the warm air produced by the incidence of solar radiation on the surrounding rocks, and this could explain accelerated shrinkage of the icy substrate (Ceballos et al., 2006). The Bolivar peak was fragmented and had higher perimeter to area ratio than the Humboldt peak in 1952 and 1998, and the Humboldt peak has experienced a dramatic increase in the perimeter to area ratio after 1998 (Ramírez et al., 2020).

Deposition of light absorbing particles from the atmosphere on snow and ice can reduce glaciers surface albedo and enhance the melting process (Gilardoni et al., 2022). Concentration of black carbon in the high elevations of the Cordillera de Mérida have been linked to biomass burning in Venezuelan savannah, with higher fire activity and higher concentration following El Niño years (Hamburger et al., 2013).

Atmospheric or aeolian deposition (windfall) provide key nutrients (e.g. Carbon, Nitrate and Ammonium) to the biota of the supraglacial zone (Edwards, 1987). Nutrients and meltwater can be transported through interglacial cracks and crevasses to reach the subglacial zone, where it combines with small particles produced by rock comminution (Hotaling et al., 2017). Englacial and subglacial biota of this ecosystem are still undescribed.

The role of the supra- and subglacial microbiota on the exposed glacier forefield is currently under study in the Cordillera de Mérida. The pioneer lichen and bryophyte species might have a facilitation effect on the long-term establishment of wind-dispersed and -pollinated vascular plants (Llambí et al., 2021).

5.2 Threats

The two main threats to the Tropical glacier ecosystem of the Cordillera de Mérida are climate changes and severe weather, and pollution by air borne pollutants (Table 5.1).

Reconstruction of glacier advances in the last 1500 years highlights their sensibility to natural changes in climate, and this has likely been magnified by the human influence on climate (Polissar et al., 2006). The effect of increasing temperatures and decreasing precipitations on the venezuelan glaciers over the last decades has been discussed by Braun & Bezada (2013). Evidence suggests that this is an ongoing threat affecting the whole distribution of the ecosystem and is likely to cause rapid declines.

Although pollution by light absorbing particles could account for up to 22% of albedo reduction in parts of the tropical Andes (Gilardoni et al., 2022), the effect of such pollutants in the Cordillera de Mérida have not been measured (Hamburger et al., 2013). Thus the scope and severity of this threat are not known.

| Threat classification | Timing | Scope | Severity | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ongoing | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

|

Ongoing | Whole (>90%) | Rapid declines | High Impact |